Simon’s answer to Planet Patient vs Planet Researcher

“She’s really ‘leuk’ (Dutch for nice).”

Diagnosed at 46 with Parkinson’s, Mariëtte keeps a great blog that touches on many areas of life, including boxing. But it also provides her with a medium to discuss how she lives with Parkinson’s (you should follow her if you don’t already).

In a recent post on her blog – called “Planet Patient vs Planet Researcher” – Mariëtte asks ‘are we really so very different, we patients and researchers?‘

By Simon Stott. Researcher who makes the unusual effort of explaining the science and research that is currently being conducted on Parkinson’s disease in plain English. He made an even more unusual effort by writing an answer to my blog “Planet Patient vs Planet Researcher.”

From his site The Science of Parkinson’s

From his site The Science of Parkinson’s

About Simon Stott

My name is Simon, and I have been working in the field of Parkinson’s disease research for over 15 years (both in academia and biotech). I am currently a research associate in the department of Clinical Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge (UK), in Prof Roger Barker’s lab. I conduct both lab- and clinic-based research on Parkinson’s disease (including the Parkinson’s UK/BIRAX breath analysis study). I am also the president of my local Parkinson’s UK support branch in North Hertfordshire. All views/opinions expressed here are solely my own, and do not reflect the views of my employers, funders, or associated parties.

Her answer is ‘Yes!‘ and she listed 10 areas where the differences are apparent. Mariëtte’s points are made from an educated point of view – she is a very dedicated Parkinson’s research advocate.

Reading through her post, however, I saw it as a nice opportunity to provide the view of things from the other world (Planet Researcher). So, with her permission, I have copied her 10 points here and I have tried to provide a Planet Researcher view of her thoughts (below in red). And I should add that I do not speak for everyone on Planet Researcher – my views are simply that: mine. My comments on Simon’s comments are in green.

Planet Researcher to Planet Patient, by Simon Stott

Are we really so very different, we patients and researchers? Yes! (No) And here’s why:

Feeling

Patients know what it feels like to have Parkinson’s. Researchers (typically) do not.

Simon: Planet Researcher completely agrees. But the opposite statement can also be made: “Researchers know what it feels like to be a researcher. People with Parkinson’s (typically) do not.

Mariette: we do however know full well what it is like to live on Planet Work. Many of ‘us’ live on both Planets.

Progression

Patients fear the progression of their disease. Okay, maybe not all of us, but we don’t exactly look forward to it either. In contrast, researchers have nothing to fear – they largely control the progression of their research themselves.

Simon: I think it is fair to say that the inhabitants of both planets share a common goal: Self-preservation. And fear is definitely a shared trait between the two.

Mariette: On Planet Patient we have very little control over the progression, resulting in fear of loss of control over health AND work.

But first, on the subject of control: It is important for Planet Patient to understand that researchers do not have much control over the progression of their research. The progression of one’s research is influenced by numerous factors that are out of the control of the researcher. For example:

- Funding agencies don’t fund a project, which slows things down.

- Experiments go wrong, which slows things down.

- Using different types of cells or reagents can affect or completely change results, which slows things down.

- Regulators drag their feet, which slows things down.

- Administrative red tape is forever increasing, which slows things down.

- And the very nature of science slows things down.

On Planet Researcher, we don’t move from fact to fact in a clear linear path with research. If anything, we go from suggestion to suggestion. And sometimes this can lead to dead ends (which slows things… you get the idea). At best – in that the fuzzy, grey area that is called the ‘very leading edge’ of research – a researcher is basically shining a torch out into the darkness, and trying to decipher what they see. And sometimes what they observe makes no sense, based on previous results or what is currently known. This last part is both exhilarating and terrifying for a curious mind.

‘Exhilarating’ because in the 125,000 generations since the first Homo species appeared, you could be the first person to witness something truly novel. It is akin to Armstrong walking on the moon, knowing that as you look down the microscope, no one has ever possibly seen what you are looking at. And it can be ‘terrifying’ because you have to be able to explain whatever it is that you have discovered before your research funding runs out, if you are hoping to get more funding to continue doing what you love.

And as all of this is going on, the relentlessly increasing pace of progress on Planet Research is such that most researchers ultimately get left behind as their area of interest falls out of vogue. How do you maintain the research funding for your tiny area of interest, if the attention has shifted elsewhere?

Adding to this state of anxiety, the longer you manage to hang around on Planet Researcher, the higher the stakes.

Mariette: Same goes for Planet Patient.

A research grant (which funds a project) typically doesn’t last longer than 3 years, but during those three years a lot of stuff can happen in the life of a researcher. Outside of the lab, they may fall in love, have kids and (try to) buy a house. At work, they will employ support staff to help do the research and the department will ask them to take on students in their lab. But 12-18 months before they finish their grant, the researcher will need to start looking for the source of funding for the next 3 years (to support the kids, the mortgage, the staff, and the students that they have taken on).

Mariette: This one hurts a little: ever seen a yopd who is NOT worried about the financial (and physical) ability to support the kids etc?

This is the cycle of seasons on Planet Researcher. Summer is defined as a period of good funding for the lab, while winter is when the money dries up. And winters can be long and hard. Oh, and lest we forget that the industry-component of Plant Researcher, which doesn’t fare much better. The hours are less, the salary are slightly better, and the necessity of grant funding is not so intense, but the job security is questionable at best. A clinical trial fails and your company gets shut down. A board meeting decides the R&D budget is better spent on other projects, and your department is given redundancy notices. And the kids, the mortgage, and the staff issues all apply here as well.

This is not to paint a bleak picture of the situation on Planet Researcher – it is a wondrous and fascinating place to live – but rather to point out and share some of the common aspects of life on the planet. And luckily there are enough people living on Planet Researcher that major progress is being made in Parkinson’s on numerous fronts.

Take home message: Planet researcher also has fear and its inhabitants regularly feel like they have very little control.

Bedtime

Patients cannot simply remove their Parkinson’s at bedtime. They can’t make a mental note to self: Right, I’ll pop these pesky symptoms in the wash basket, hang these ones up on a coat hanger and tidy that other 50 away. Researchers, meanwhile, CAN shed their lab coats at bedtime. Once safely tucked up in bed, you can no longer tell that they’re researchers.

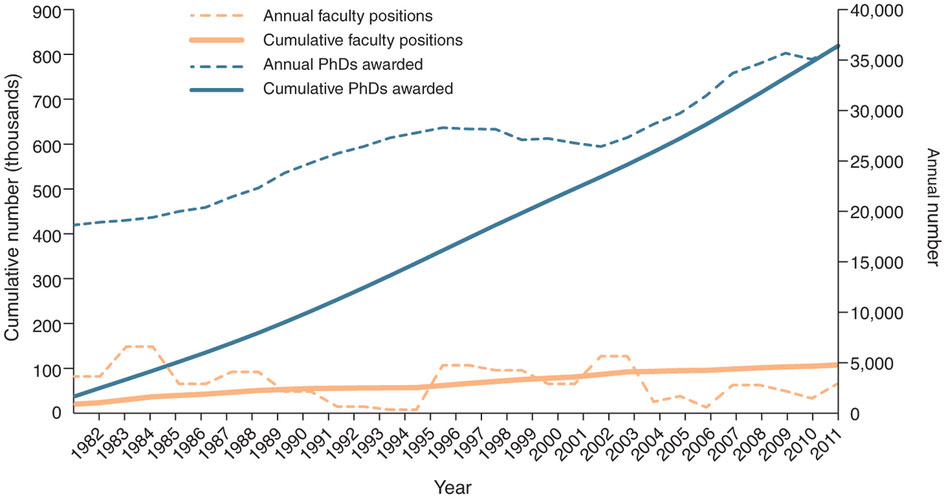

Simon: Once safely tucked up in bed, inhabitant of Planet Research usually can’t be differentiated from the inhabitants of Planet Patient because they too have trouble sleeping. The researcher will lie there worrying about their research (particularly the funding of it). Worrying about reviewer comments on their latest manuscript, the feedback on their next performance review, and (of course) their future job prospects. And the latter is a major issue for young researchers. A terrible truth for all of the young scientists in training at the moment is that there are few if any jobs waiting for them in academic research. Between 1982 and 2014, almost 800,000 PhDs were awarded in science and engineering fields in the USA, but only about 100,000 academic faculty positions were created in those fields within the same time frame (Source).

This demoralising aspect of life on Planet Researcher (the lack of job opportunities) makes life very hard for senior researchers who are trying to encourage smart young people to come to Planet Researcher (rather than Planet Finance). And once some of those young people do sign up to do the research, how to keep them motivated? The novelty of ‘walking on the moon’ wears off after a while, and smart young minds start looking off planet for opportunities with better career advancement (better salaries on Planet Finance, or so I hear). Planet Research can become a lonely place as one’s friends all disappear off world for greener pastures.

Longevity is a real issue on Planet Researcher. My guess is that the average time spent on Planet Researcher is 5 years (project students come and go very quickly, and many people do not hang around after being awarded their PhD). Thus the momentum for Parkinson’s research is largely maintain by a few lucky long-termers. But the skills and expertise that are learnt by the short-stay individuals are easily lost.

These are just a few of the things that keep folks awake on Planet Research

Mariette: as a director of a fintech company I can relate to having work trouble keeping you awake.

Work

5 years into Parkinson’s and patients can count themselves lucky if they’re still able to do the same job. 5 years on and some things will have inevitably bitten the dust. 5 years into their glittering research career and researchers can count themselves lucky if they’re not still conducting the same research. Hopefully, their work is bigger and more important than ever.

Simon: 5 years into a research career focused on Parkinson’s and the researcher can count themselves lucky if they’re still able to do the same job. The really lucky ones will have their first academic faculty position, but this largely depends on your definition of ‘lucky’. The first academic faculty position usually results in less actual research being done:

And many inhabitants of Planet Researcher will not get their research funded which means that they miss out on that first academic position, and they will be forced to leave the planet they love and have called home for the first parts of the career. And they will seek employment off planet in jobs that don’t necessarily inspire them as much (but hey, at least the pay/hours/levels of stress are better).

Training

You’ve not only got 7 million Parkinson’s patient variants, you’ve also got 7 million socio-economic variants. One patient has a scientific education in physical geography, one in chemistry and another no education at all. What you might also forget is: that only a portion of people with Parkinson’s speak and read English. Researchers certainly wouldn’t be researchers without their academic training and they definitely wouldn’t be able to publish their trailblazing papers if they couldn’t speak or read this global lingua franca.

Agreement here between the planets.

Visit

If you’re on Planet Patient, you can do one of two things. You can wait and see what the doctor prescribes. Or, you can take a hop, skip and a jump to Planet Researcher. Opt for the latter and you’d better not differ too much from the researcher in terms of point 5. Otherwise there won’t be much to communicate, let alone learn. And, let’s not forget; researchers tend only to issue visas to Planet Researcher when they need a patient or an entire cohort of patients, for some important trial or another. As a patient, you can only hope that you’re permitted to enter prior to the trial’s design

Simon: This is actually a fair point.

Mariette: So are the other ones, I hope? (joking).

Another point of interaction between Planet Researcher and Planet Patient is where researchers ask one or two of them to read the lay person summary on their grant application so that they can tick the box on the application that is labelled “Affected individuals have read it”. More diplomacy and trade links between the two planets are required.

And opportunities are being missed. For example, one can only wonder how long it would have taken researchers to ask themselves if Parkinson’s has a smell. Without the idea being pointed out to them by members of the Parkinson’s community (Click here to read more), we would probably still be waiting for a researcher to ask the question.

Which begs the question: What other gems are being missed?

Mariette: is there only 1 type of dopamine?

More inter-planet visits should definitely be made.

Gold

Some inhabitants on Planet Patient are frantically searching for ‘gold’; that one miracle cure that will rid you of your Parkinson’s forever. But usually there’s nothing else for it than to swallow what everyone else is swallowing and to exercise until you drop. On Planet Researcher, the average researcher has just one thing on their mind; to be the first to find that gold. To publish ground-breaking research under their name. It’s an extremely competitive place, Planet Researcher.

Simon: Planet Researcher is a very competitive place. So is Planet Patient. We are competing with time. And publishing high impact research is the only measuring stick. But at the end of the day, even that is not a silver bullet for surviving on Planet Researcher. You can follow the advice of others – work like mad/publish high – and still end up with no research funding, no access to facilities and no job.

But this is actually a good thing.

We need to maintain a high bar and allow no rot. There should be no half measures. And anyone moving to Planet Research should fully understand that dropping the ball results in a one-way ticket off planet. That might sound harsh, but doing research is not a right. It is an amazing privilege that society bestows to the lucky few who want to explore an area of interest. A community giving an individual a chuck of money and saying “here, see what you can do”, is a beautiful thing and an incredible honour. And it is important that inhabitants of Planet Researcher always appreciate and respect that.

And setting high standards is one way of doing that.

Money

You saw this one coming: money. You certainly don’t earn any money on Planet research and your income is constantly under threat. Visits to Planet Researcher are paid for out of your own pocket and conducted in your own time. But I’ve yet to meet the first researcher who works ‘pro deo’. This is a massively underestimated difference between the two planets. The currencies are completely unequal. And I’m afraid that this makes the patient subordinate to the researcher. It’s not only knowledge that’s power, but money too. You can say what you like about patient participation, engagement and goodness knows what being so fantastic, but if you’re not prepared to pay for it, then what’s it really worth to you?

Simon: Agreed. The money on Planet Researcher sucks.

Some of my city boy friends earn more in their annual bonus than the average inhabitant of Planet Researcher does in a year. Long term maybe that will be detrimental, but that is part of the choice everyone makes. And for the record, there are many people on Planet Research who work pro deo/pro bono. They are the truly hardcore – ‘the blindly committed’. They have drunk the cool aid and simply can’t walk away. I think part of every researcher can relate to them, whether they follow that path or not. Many of the pro bonos come in the form of individuals who simply want to finish what they started after their contract has finished. An effort to pay back that gift from society. It is a process that can often take a long time and be very taxing.

And then there are other pro bonos, whose funding dried up and they lost their position but simply don’t know what to do with themselves. They don’t want to leave Planet Researcher. It is all they have ever known.

Visits to Planet Researcher from Planet Patient can be funded by research projects, where travel costs have been included in the grant. But one of the most inspiring aspects of the Parkinson’s community (from my personal point of view) is the number of participants who chose not to claim those costs.

Mariette: You do not know how many inspiring participants you missed, simply because they could not afford participation.

I have recently become a big fan of Lao Tsu (founder of philosophical Taoism), and one of my favourites of his ideas is to ‘act without expectation’ (harder than it sounds). This doesn’t mean bankrupting oneself for the common good, but it certainly reduces the chances of being disappointed and frustrated. Oh, and the patient is never subordinate to the researcher for one simple reason: The latter can not exist without the former

Free choice

I don’t think I need elaborate on this particular point…

Simon: I think I need elaborate on this particular point…

There may be a particular aspect of biology that really rings the bell of an individual researcher, but if they can not get funding for the idea, they are usually forced to focus on other ideas that do get funded. On top of this, academic departments will require the researcher to help out with department administrative duties which further lessen the feeling of free choice.

Mariette: I’d prefer your lack of free choice.

Advocates

Parkinson’s Research Advocates try with all their might to influence the orbit of Planet Researcher. But who are their opponents…or team players if you prefer? Is Planet Researcher populated with multitudes of Parkinson’s Patient Advocates? Other than the paid ‘Patient Participation Officers’?

Simon: Here is the controversial statement of this post: Parkinson’s Research Advocates of Planet Patient need to have more impact beyond simply calling themselves ‘Parkinson’s Research Advocates’. They need to propose and force through actual changes. To be fair, the cultural climate on both planets is too conservative. On Planet Researcher, the facts of life described above have led to a focus on safe, do-able projects that will definitely provide subtle steps forward and may have more impactful, accidental discoveries along the way. There are very few high risk leaps of faith. Where are the Barry Marshalls? (Click here to learn about him). What happened to the Werner Forssmanns? (Click here to learn about him).

And the same could be said about Planet Patient. Tom Issacs walked the entire coast line of the United Kingdom to raise money and awareness about Parkinson’s, and then helped to co-found a charity dedicated to finding a cure for the condition (the Cure Parkinson’s Trust). Where is that kind of effort being made by the ‘Parkinson’s Research Advocates’?

(Ooohh, these words are going to get me into trouble! But hey, if they stimulate a bit of constructive discussion and maybe more action, it’s worth it).

Mariette: They are indeed getting you into serious trouble. Tom Isaacs was exceptional. So was Einstein.

The two planets collide

The good news is that we’re all just people, who all want the same thing. Only you’ve got a different concept of time on Planet Patient. Trials can take years and years, and by the time a new pill rolls out, you’re dopa has dried up. The 10 differences above are likely nothing new to you researchers. But please bear them in mind when devising your research programs. Come visit Planet Patient. And ask the local inhabitants: what can I do to help?

Simon: Hear, hear!

Any comments or thoughts below would be greatly appreciated. Alternatively, you could contact me directly. And again, my comments here are my own. Many of my colleagues will disagree with certain things I have written here, which I appreciate and respect. But the same could be said for those on Planet Patient. Each of our experiences will be different. In addition, my comments here were not intended as a rebuttal to Mariëtte’s brilliant post. I simply thought it might be useful for the Planet Patient community to view life on Planet Research. And finally I hope I don’t come across as cynical and jaded. I love life on Planet Research, and can easily see myself becoming one of those pro bono types I mentioned above. For I have sipped deep on the cool aid.

Mariette: thank you Simon, I love your blog, I love our disagreements. Come and visit Planet Patient soon!

Comment by Kevin McFarthing

Wow – well done Simon and Mariette. Two really good articles and a great debate.

Of course, people on Planet Patient are impatient; of course, work on Planet Research takes time. Ultimately, it’s the results that count, and quite frankly, if a researcher produces a great paper that moves us closer to a cure, I don’t care if it’s through their devotion to the cause of Parkinson’s patients, or their desire to reach the next step on the career ladder.

There is also a danger in focusing too much on a cure. Yes, I know this is counter-intuitive. Often, though, curiosity leads people on Planet Research down interesting paths. Kohler and Milstein were creating hybridoma cells, not focusing on generating monoclonal antibodies. There are many more examples. There should be time, space and cash to follow observations prompted by “that’s interesting”.

So, as a resident of Planet Patient, who lived briefly on Planet Research (and I’ve visited many times since), yes, we need to advocate for more change in research. But there are some caveats. Let’s advocate for more investment in research; but don’t try to tell them what to do, or to believe that we know what the priority scientific targets should be. Let’s then, support research groups in whatever way they need. Let them get on with it.

Finally, it would be good to hear from Planet Development in this series, from the people in Pharma companies who invest a lot of money to bring new therapies to Planet Patient.